Hedebo Embroidery and Flax

Hedebo Embroidery is made with linen, which is processed from the fibres of a plant called flax. The process took between one and two years, from sowing the flax seed to producing the finished linen cloth and fine linen thread. In the following section you can learn about the whole process from plant to linen: sowing, weeding, harvesting, retting, drying, breaking, scutching, hackling, washing, bleaching and weaving. Finally, the linen fabric could be embroidered with fine linen thread.

Flower of the flax

Growing Flax

Flax was cultivated on most of Denmark’s farms where the soil was suitable. It was not grown south of the Limfjord in West Jutland, nor in the infertile areas of Himmerland and Vendsyssel. In these regions, linen was purchased, or wool was used instead. Most farms were self-sufficient in producing clothing and textiles, using the wool from their sheep and the flax grown in their fields. The flax fields were sown in April or May, with the seeds planted closely together. The closer the plants grew, the better the fibers. Everyone on the farm helped with the flax fields. Farm boys, servant girls, and children all assisted in weeding the flax before it grew too long. It took a whole day for 10 people to weed 1.5 acres of land, because the weeding had to be done very carefully to prevent damaging the fragile flax. Flax was highly valued, and an old superstition held that one would never lack clothing if they always greeted the flax field when passing by. The farmer would give the servant girls a small plot of land to cultivate their own flax, which was part of their wages.

"Cotton - During the 1800’s, Denmark began to import cotton goods from abroad. Cotton is a soft fibre, found around seeds of the meter high cotton plant. The plant requires a climate with 6 or 7 months of warmth and is cultivated in India, China, The Soviet Union and USA."

Flax plants

The Flax plant

Flax has been known in Denmark since the Stone Age. It is one of the oldest plants used for the production of linen fabric. Until around 1900, nearly all farms in Denmark had large fields of flax to produce their own linen for sheets, tablecloths, shirts, and shifts (a type of undergarment for both men and women). Today, Denmark imports linen, from countries such as the Baltic states.

There are two types of flax: 1) Oil flax, used to produce linseed oil, and 2) Linen flax, used to make linen fabric. The word 'linen' is derived from the Latin word for the flax plant, linum, which in turn comes from the earlier Greek linon. This origin has led to terms such as 'linseed oil.' Linen flax is an annual plant that can grow up to 90 cm tall and produces small blue flowers.

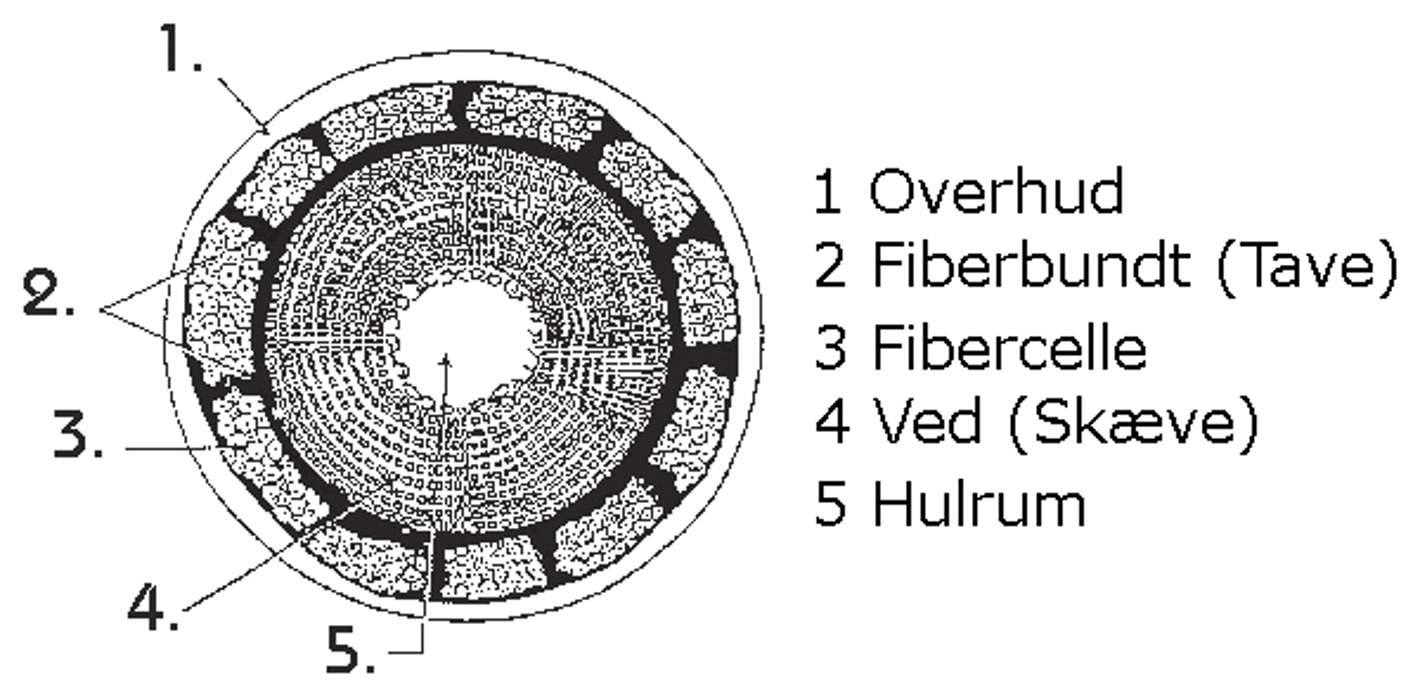

The drawing shows a cross-section of a flax stem. Linen fabric and linen thread are made from the plant's fibers, known as fiber bundles.

Drawing of cross section of flax stem. 1. Epidermis - 2. Fibre bundle - 3. Fibre cell 4. Xylem - 5. Hollow

Harvest

Flax was harvested when the seed capsules turned yellow, typically around mid-August, coinciding with the corn harvest. An early harvest produced finer-quality linen. The flax was shaken and pulled up by hand, with the roots intact. It was left to dry in the field and was only brought back to the farm after the corn harvest. At the farm, the seeds were removed using a ripple, a rough comb with tightly spaced wooden or metal teeth. The seeds were then stored for sowing the following year.

The ripple, used to harvest the flax seeds

Retting

The next stage was called retting, a process that decomposed the cellular matter binding the fiber bundles and separated the fibers from the rest of the plant. Retting caused the outer surface of the flax stalk to become porous. There were 2 methods of retting.

The first was called Dew Retting, where the flax straw was laid in thin layers on the field and left for 4 to 8 weeks. The straw was turned a few times during the process to ensure each stalk came into contact with the earth, where decomposition occurred more quickly.

The second method was Water Retting. In this process, the flax was held underwater by a stone or a turf of grass. This method took only 7 to 14 days, depending on the temperature.

After retting, the straw was dried in the field and then brought back to the farm for storage in a dry, airy location, ready for the next stage of the process.

Breaking

The flax was thoroughly dried using either a flax oven or a drying pit. The flax oven was a large brick structure placed a safe distance from the farm due to the fire hazard. Often, farms shared a common oven. Drying pits were deep holes in the ground with a fire at the bottom and a grid on top. The flax was placed on the grid to dry.

Once the flax was completely dried, it had to be broken using a flax breaker, a large wooden device with over-and-under jaws. Bundles of flax were pounded and broken from root to top by the blades. The flax was then bound into small bundles and stored dry. This procedure required many hands, and it was common for farms to share the task. It was customary to hold a "break party" with good food, alcohol, and dancing to celebrate the completion of the work.

Woman scutching flax. Photo Frode Hansen, Dansk Folkemindesamling

Scutching

The next stage, scutching, involved placing the flax on a slotted, vertical wooden board and beating it with a scutching bat to remove the broken straw. This was done by the women, working together in groups. Strong arm muscles developed after a day of scutching, and the women often celebrated the completion of their task with a scutching party.

The residue from scutching was called boon and was a mixture of straw and a little fibre. This was later spun to give a very coarse linen textile, used for example in the manufacture of sacks.

Scutching boards and bats were often beautifully decorated and were often given as tokens of love by men to their respective future wives. Scutching machines were developed from the mid 1800’s, making the task much easier. The machine had four wooden blades that were set in movement by a handle. Machines were also developed that were driven by horse power, and often several farmers from a village would share the cost of this machine. Eventually the job was done by professional flax swingers, who travelled from one village to another with their own equipment.

Hackling

Hackling was necessary before the fibres could be spun. This can be compared to combing long hair, and it produced linen fibres that were fine and shiny. In Danish the term is called “hegle” and can refer to a rough, arrogant woman. To “hegle igennem” in Danish is somewhat similar to “tear a strip off” in English.

The hackle was a block with several rows of iron pins and it was mounted on a board. Firstly the linen was pulled through a rough hackle and the waste from the rough hackle, the tow, was used for example, to make rough clothing. Next a hackle with finer and closer set pins was used, and the finer the hackle, the finer was the resulting linen thread that could be spun. The very finest of linen thread was produced from pulling 2 strands several times through the finest hackle. Hedebo Embroidery was only worked with the finest threads.

The hackled linen was gathered in locks and formed into wreaths. The wreaths were often hung in the back room until the linen was spun. Many linen wreaths were an indication of prosperity.

Woman is hackling flax. Photo Frode Hansen, Dansk Folkemindesamling.

Spinning

It was the task of the housewife to spin both wool and linen yarns on her spinning wheel. Spinning wheels were in use from the 1600’s and prior to this a spindle was used. Wool was spun before Christmas, and the linen was spun after Christmas. Linen benefitted from the storage period in order to regain its elasticity after the harsh treatment involved in the production of linen from flax. An old Danish saying is that, “With keeping, old linen turns to silk and wool to mud”.

It required great skill to spin linen and took a young girl several years to master the technique. Firstly she learned to spin wool and then she trained with the tow from the hackling process for 4 or 5 years until she was allowed to spin the fine linen. The most difficult thread to spin was the very fine linen thread used for the Hedebo Embroidery.

Woman spinning flax. Photo Frode Hansen, Dansk Folkemindesamling.

Washing and bleaching

Linen is by nature grey-brown, but with bleaching in the sun it can become snow white. It was first bleached after spinning, where the thread was washed in a solution of water and fine ashes from pure beech wood. The same method was used for washing linen clothing. Finally the yarn was rinsed and beaten with a washing bat before being hung on a stand to complete the bleaching in the sun. Bleaching took place from March to mid summer, where the sun was strongest. The linen yarn was then ready to weave.

"Bleaching - In Copenhagen there is a street named “Blegdamsvej”. It is named after meadows which were used for bleaching linen from the 1600’s-1800’s. Today the linen is bleached by a chemical process."

Weaving

The bleached linen thread was woven into linen fabric. The thread was delivered to the weaver. In rural districts, a small holder or his wife would earn a little extra by weaving for the village farms.

Bleaching marks

After weaving, the linen fabric was bleached once more. Bed linen, table linen and clothing had to be pure white. They were washed in a solution of ash and spread out in long lines on a grass meadow. Straps were sewn on to the fabric enabling it to be pegged to the ground with wooden pegs. The linen lay for some time in the field and it was necessary to prevent geese and cattle from walking over the fabric. It was also important to guard the linen from thieves, and in some regions young girls or farmhands kept guard over the fabric during the night. This could not have been an enjoyable task.

When the fabric was sufficiently bleached, it was rolled up and stored for sewing in the farmhouse chests. The chests stood in the cool back room of the farmhouse and the more chests, the better! They were the equivalent to a bank box and contained a great deal of the material wealth of the farm, which was indeed valuable. There was linen cloth, fine clothing, Hedebo Embroidery, bed linen and linsey- woolsey (combination fabric often striped, with linen warp and wool weave). At the end of the 1800’s the value of a farm’s household textiles was calculated to be equivalent to 16 cattle.

Woman weaves flax linen. Photo Frode Hansen, Dansk Folkemindesamling.